When Words Come Back

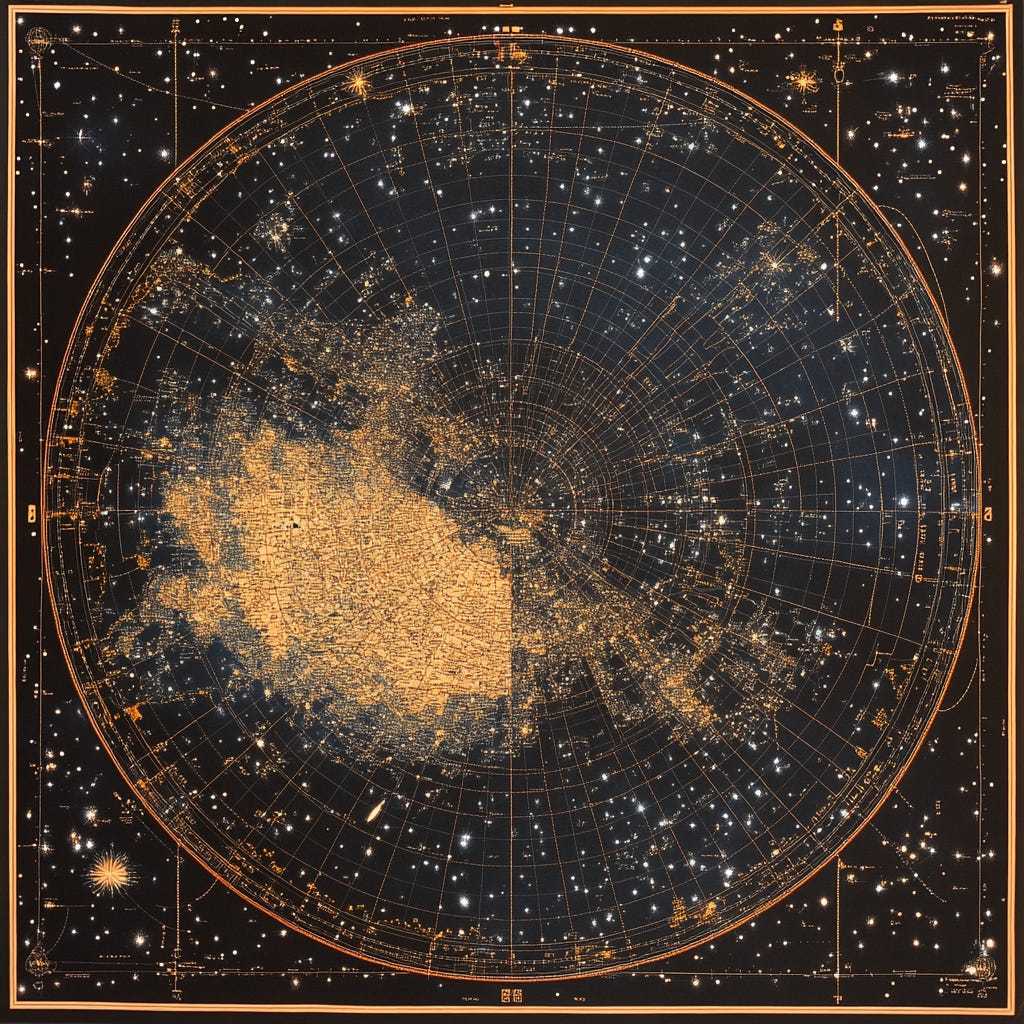

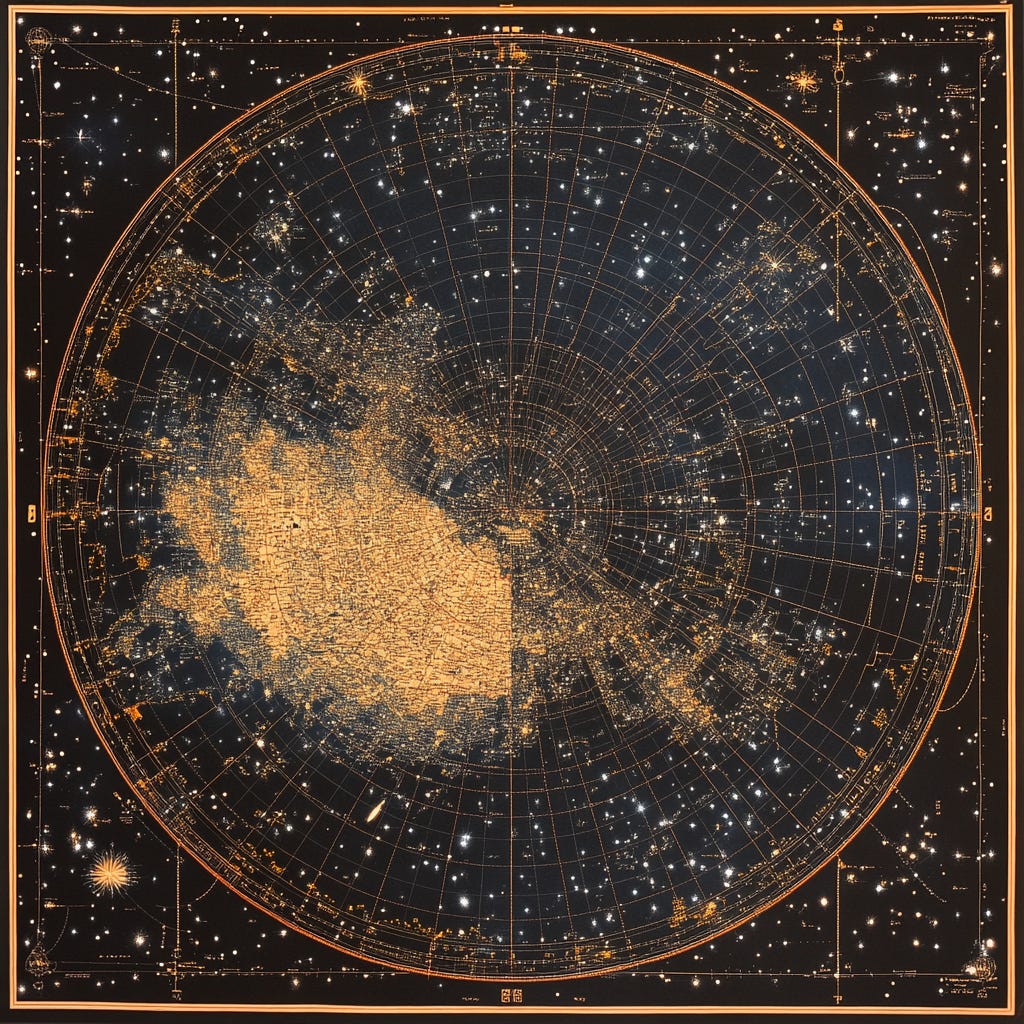

Mapping the Geography of Grief

When the words finally returned, they came like migrants—first a few tentative scouts, then suddenly, in waves. After months of silence, I recognized their arrival as what Toni Morrison once described: that vital translation of experience into art, the thing that sustains us, heals us, makes meaning possible.

After months of silence, I am back with words.

There are territories within us that no map can chart, vast continents of experience that resist language. I discovered one such realm last year when my mother died—a landscape of grief so vast and varied that words seemed to shrink in its presence.

When death enters your life, it demands space. It clears your calendar, empties your mind of daily concerns, and creates a vacuum where words used to be. Having lost my father years before, I thought I knew this territory. But grief, I've learned, is never the same country twice. This time, I had to be not just a mourner but a guide, helping my children navigate their own unmapped sorrow.

My son's grief, in particular, exists in a place beyond language. It surfaces unexpectedly during quiet moments—while watching TV together, in the comfortable silence between mother and son. Without warning, the continent of his loss rises like an island from the sea. In these moments, I witness how grief in the young takes shapes that even they can't describe, expressing itself in silence, in presence, in the simple act of being together.

We all carry these internal continents, these vast territories of experience that resist translation into everyday speech. These territories hold more than just sorrow—they contain our deepest joys and most fundamental fears. We inhabit these spaces alone, even in crowded rooms, like travelers in a country only we can see.

Yet humans, persistent cartographers that we are, keep searching for ways to map these territories. A melody becomes longitude, a brush stroke latitude. We plot our grief in minor keys, sketch joy in vivid colors, measure depth of feeling in meter and rhyme. This is what Morrison meant by functional—art doesn't just express our experience, it helps us navigate it. When we're lost in these internal landscapes, a song or painting can become our north star or serve as our diplomatic corps between the speakable and the unspeakable. When direct translation fails, art creates a new language, one that can carry the weight of our most profound experiences.

Derek Walcott wrote, "No nation but the imagination." Perhaps he understood that our internal territories—these continents of unsaid things—can only be fully explored through the passport of imagination. It's in this borderless country that we can finally give shape to our shapeless experiences, voice to our voiceless emotions.

My son may not have the words for his grief yet, but he has found other ways to inhabit it. Sometimes it's by texting his grandmother, hoping the messages he sends reach her, in a new kind of celestial cartography or playing soccer with his friends where the spirit of how she made him feel is alive and well. These are all valid ways of mapping the unsayable and as a parent I am learning how to just sit with it all and resist every urge I have to make his pain go away. Living with grief is a constant learning and releasing.

As I write this, I'm aware of the paradox: using words to describe what cannot be put into words. But perhaps that's the point. Like early explorers drawing the edges of unknown continents, we can at least sketch the outlines of these internal territories. We can leave markers for others who might visit these same lands of loss, love, fear, or wonder.

In the end, these territories may not be as unmappable as we think. Each generation adds to the chart—from cave paintings to text messages, from tribal songs to TikTok videos. My son's celestial texts to his grandmother are just the latest coordinates on an ancient map, one that humanity has been drawing since we first looked up at the stars and wondered where our loved ones had gone. In these shared attempts at charting the unsayable, we find our truest connections.

And now that my words have returned, they arrive like a tide, insistent and unstoppable. There are more stories to tell, more territories to map, more silences to explore. I am back, and this time, the words won't wait

.

This is so beautiful, thank you Mehret. I feel like as a society we make almost no space for grief, public or private. We need to.

As always, Mehret, I'm inspired. Your brilliant, creative, rich, soulful insights -- about grief and beyond -- are such a gift that you share with all of us. I will continue to return to this beautiful substack. Thank you.