“The proposition that history is another form of fiction is almost as old as history itself, and the arguments used to defend it have varied greatly.” - Michel-Rolph Trouillot

If the art and war of story hinges on verisimilitude, as I discussed in my last post, the best expression of this relationship may very well be history.

Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History is a book by Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot that explores the ways in which historical narratives are constructed and how power dynamics influence what gets included and excluded from those narratives. Trouillot argues that history is not an objective and unbiased account of the past but is shaped by various factors, including the perspectives of those who write it and the social and political context in which it is written.

One of the central concepts in the book is the idea of "silencing," which refers to the process by which certain events, voices, and perspectives are marginalized or excluded from the historical record. Trouillot examines how silencing can occur through various means, such as through the omission of certain facts, the distortion of events, or the prioritization of certain voices over others. He also emphasizes that silencing is not always a deliberate act but can be the result of structural factors and ingrained biases.

Trouillot's book challenges traditional notions of history and highlights the importance of recognizing the limitations and biases inherent in historical narratives. It encourages readers to critically engage with the past and to consider how power and privilege shape our understanding of history.

Silencing is one of the most powerful effects that doing things with stories does. Examining how this happens at the institutional level, at the community level, at the family level, and at the individual level, reveals that silence is often the product of larger forces foreclosing the possibility to speak. These same forces make it difficult for certain kinds of stories to get written, made, and/or circulate.

Trouillot’s book is one of the texts that the pioneering Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck drew on in the HBO documentary series Exterminate All the Brutes. Peck's 4-part hybrid docuseries explores the history of colonialism, racism, and genocide. The series is structured around four central arguments:

1. The Myth of Progress: Peck argues that the commonly held belief in human progress is a fallacy, as it often overlooks or downplays the immense suffering and brutality that have been part of the historical march of civilization. He challenges the idea that European colonialism brought enlightenment and civilization to the world, highlighting instead the violence and exploitation that accompanied it.

2. The Legacy of Colonialism: The series delves into the deep and enduring impact of colonialism on the present-day world. It demonstrates how the legacy of colonialism continues to shape global power structures, economic disparities, and racial hierarchies. Peck contends that many of the problems facing society today can be traced back to the historical injustices perpetrated during the era of colonialism.

3. The Connection Between Racism and Genocide: Peck explores the interconnectedness of racism and genocide throughout history. He argues that the dehumanization of certain racial and ethnic groups has often been a precursor to acts of genocide. The series emphasizes the importance of confronting racism and discrimination to prevent future atrocities.

4. The Role of Narratives and Storytelling: Throughout the series, Peck reflects on the power of storytelling and the narratives that shape our understanding of history. He challenges mainstream narratives that whitewash the darker aspects of history and calls for a more honest and inclusive reckoning with the past.

These four arguments also trace how fiction becomes fact. Both Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History and Exterminate All the Brutes highlight another potent example of stories doing things - they create authority. Deciding which stories become official and which stories circulate at scale is how conceptions of reality become authoritative. Focusing on how stories make authority helps us view stories as symbolically rich resources that are constantly marking who we are and where we are in the pecking order. The advantages and benefits that stories confer in the form of authority, and status therein, can generate inequality as much as reinforce it through symbolic profit.

Pierre Bourdieu's concept of symbolic profit (1982) is a key element in his theory of social and cultural capital. Symbolic profit refers to the advantages and benefits that individuals or groups accrue in society through the possession and utilization of cultural and symbolic resources. These resources can include things like education, language skills, knowledge of art and culture, and social connections. Bourdieu's concept of symbolic profit highlights how social hierarchies and inequalities are not solely determined by economic factors but also by the ability to navigate and leverage cultural and symbolic resources. In this way, symbolic profit sheds light on the ways in which culture and social distinctions play a crucial role in shaping social dynamics and reinforcing existing power structures.

Stories are symbolically profitable and concentrate symbolic capital. Symbolic capital accrues with time. The way stories accumulate over time to form a shared understanding about history has also been referred to as narrative accretion. The longer stories circulate, unchallenged, the more likely they become authoritative. And when new stories get told that attempt to supplant conventional understandings about shared history, authority is policed by the various institutions and cultural custodians that have a stake in who has the final say.

For example, questioning prevailing historical narratives and confronting uncomfortable truths about the history of colonialism, racism, and genocide has recently come under attack. Consider the maelstrom Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project stirred for reframing American history so that the history of slavery is not elided from the founding of America, or the book bans across the country. Intellectuals and everyday people vehemently oppose the re-telling of America’s story despite the fact that the history of slavery is irrefutable. These examples are current reminders that silencing forces are very much alive and that believing the fictional parts of the past is still preferred by many.

What this demonstrates is that the collapsing of fact and fiction is often how public stories about the past are told. Against this backdrop, using stories to untell lies cannot rely on fact alone.

So what? What does all this mean?

One of the most profound findings in the The Fragile Real study was the finding that audiovisual makers using fictional stories to shift the world preferred fiction to documentary because it was more honest. As one Kenyan filmmaker put it: “With fiction, you know who is writing it and what frames it. Whereas documentary has long been a colonized format controlled by outsiders in our name.” This filmmaker is referring to a long history and tradition of telling stories about Africa that only includes the catastrophes. Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie popularized this sentiment in her viral Ted Talk The Danger of a Single Story.

Another filmmaker interviewed for the study talked about fiction being more honest in the context of our algorithmically mediated online engagement. “Yeah, I mean in a way, I think what we used to call real is so fragile now. It’s been so abused for all of the things you just said, and in a strange way that means that fiction is in some way coming across as more honest, because at least you know where you're at, right? Like I know if I watch a drama, and again it might be based on someone's true story, but it's fiction. Whereas, when I'm in the reality space. I don't know any more … why is it that that ended up in my inbox or on my feed or whatever it is and how much that's been affected by algorithms or filter bubbles and bla bla bla bla bla. And so I just feel I can be more overtly or covertly abused by the so-called real, right, then I can in fiction. You know so far as I still know the difference.”

Another maker problematized who gets to decide what is real: “Something can be true, can be real, and not factual. Because again, we have a fact making bureaucracy. We have the gatekeepers that will tell you what is fact, right fact is what institutions are built on, facts are what systems are built on and they become rigid and solidified in order to forward the functioning of an institution or a system. Real is always in flux. What is real, what is true today, for me, may not be true in one year. That’s why fiction is huge for us.”

These selected excerpts point to why fiction is realer than real.

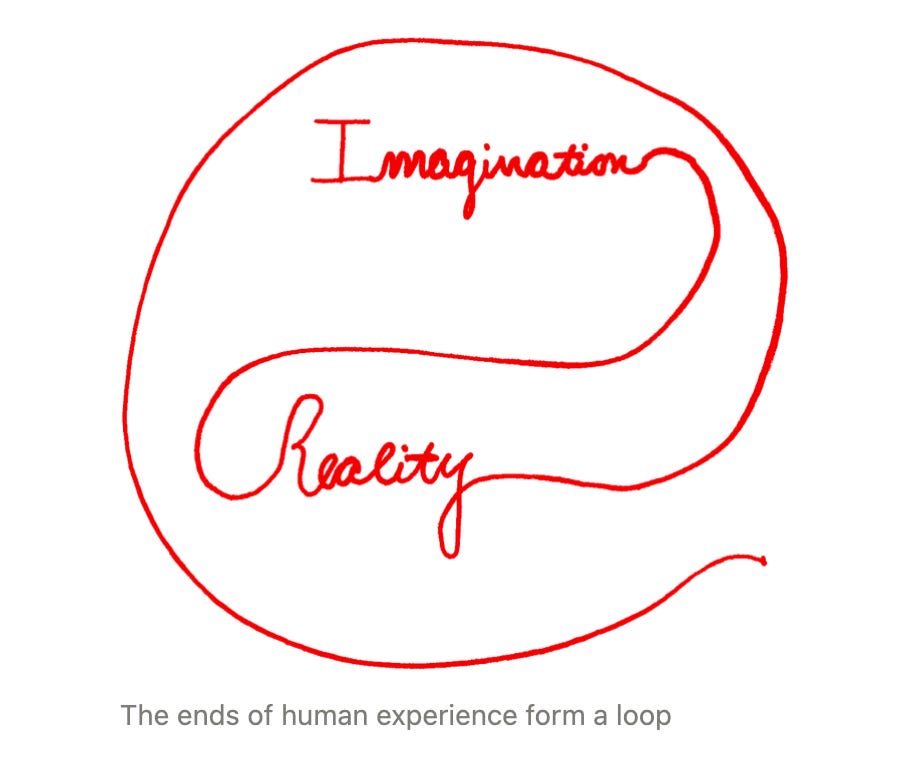

Though reality is always in flux, stories help stabilize our conceptions of reality so we can see it for what it is and let go of it when it shifts. In this context, fiction presents the opportunity to define what reality is and to whom in ways that other genres do so less effectively. What all of this reveals is that fictional storytelling is not about escaping reality but rather grappling with it and living in it.

Fictional stories reflect conceptions of the world and provoke us to consider what reality is based on. They bring into consciousness the things we can’t say and often show what our individual minds may not see on their own. Fiction is a diagnostic category to investigate society and help make strange what we take for granted about the very topics we are aiming to shift and change. This makes it a prescient tool for narrative shift and building a better future. In a world of honest lies (go to 08:58 in clip), fake news, and alternative facts, the perspective fiction brings is refreshingly clear - a point of view that can be clearly named.